00off_ÇEVRE DUYARLI MİMARLIK!

Thanks to Dr. Serpil Çerçi of Çukurova Üniversity, Shoreditch Station features as an example of ‘çevre duyarli mimarlik’ or environmentally sensitive architecture in the 50th anniversary edition of Mimarlik, the Turkish architectural magazine.

The theme of çevre duyarli mimarlik, is increasingly important given the rapid pace at which the Turkish government has launched urban redevelopment projects. The prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has promised an array of mega-projects including a 25-mile canal between the Black and the Marmara seas as well as two new cities on both sides of the Bosporus, each housing at least 1 million people – the centre of his election campaign.

“We need to face it,” Topbas said in a press conference after the devastating 2011 earthquakes in Van that killed 644 people, “we need to rebuild the entire city.”

Now the Turkish government is preparing a new law that will grant the prime minister and the public housing development administration sole decisive power over which areas will be developed, and how. The law will overrule all other preservation and protection regulations, and allow the government to declare any area in Turkey a zone of risk. Affected house-owners will have the choice of either demolishing their buildings themselves, or letting the government do it for them – in exchange for compensation. The law’s advocates argue that it will enable the government to make cities safer against the ever-present risk of earthquakes without a lengthy legal process. However, a growing number of critics point out that it will serve as a pretext to open valuable land to speculation, and drive low-income groups from city centres.

And the government’s appetite for ever more ambitious development projects is not likely to be sated in the near future. According to the Turkish Contractors Association’s predictions, the construction sector, which contributes about 6% to the economy, faces decline and much fiercer competition abroad in 2012: domestic urban renewal projects, estimated to generate £250bn of profit – £55bn in Istanbul alone – are seen as a convenient alternative. Professor Gülsen Özaydin, head of the urban planning department at the Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts Istanbul, says: “There is no urban planning that sees the city as a whole. Projects are completely detached from one another, and take no heed of the existing urban fabric, or the people living there. That’s very dangerous for the future of a city.”

According to Resistanbul, the demolition of Gezi Park – the issue which sparked the current protests – is a part of a wider urban redevelopment project in Istanbul that includes building a shopping centre which Erdogan says would not be “a traditional mall”, but rather would include cultural centres, an opera house and a mosque. The plan also includes rebuilding an Ottoman-era military barracks near the site and demolishing the historic Ataturk Cultural Centre and some see this as having historic symbolism, as the barracks were the cradle of a pro-Islamic, pro-Ottoman mutiny in 1909.

127sho_National Geographic reveals LU

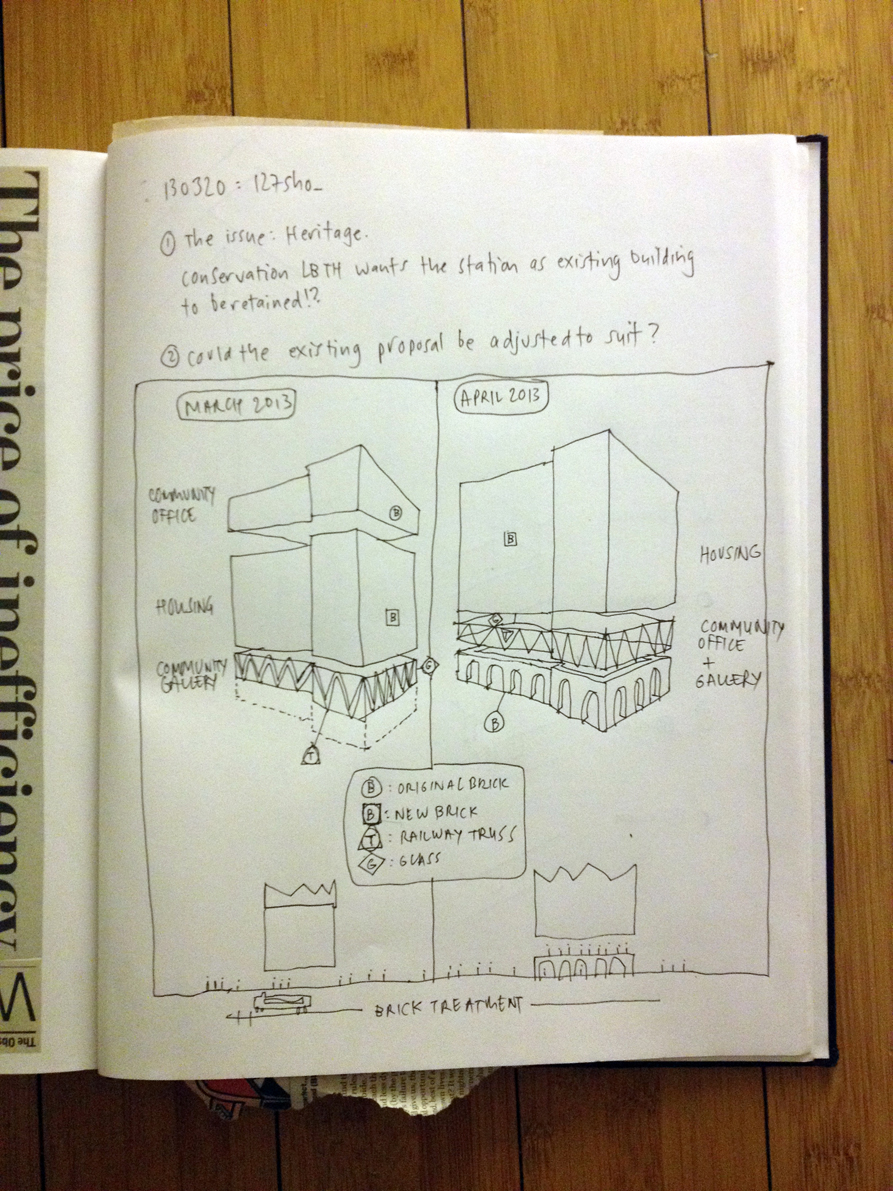

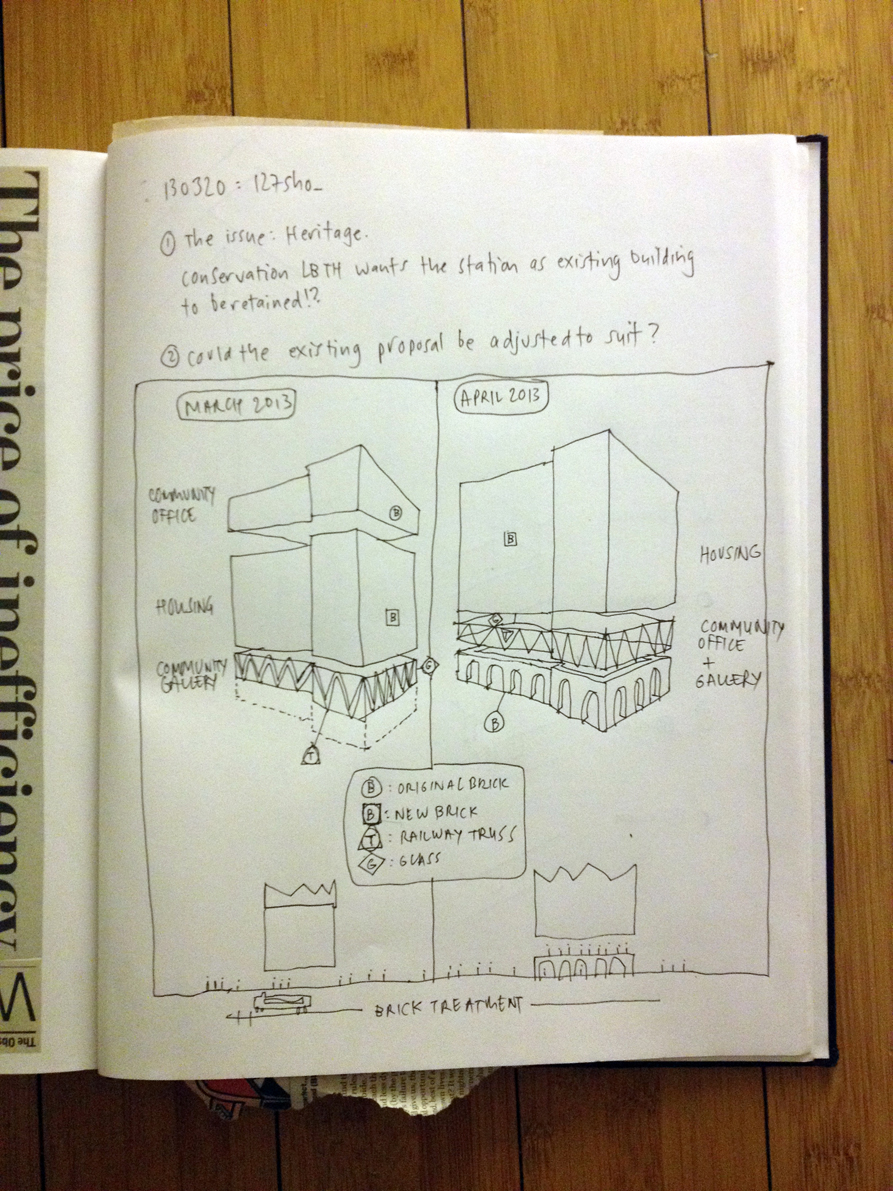

The history of the underground makes us think that the history of Shoreditch Underground Station is one of balancing mobility, housing and infrastructure. Could the architecture of the railway arches be used to support housing: sustainable conservation is in the balance. A re-think is always useful.

127sho_HOUSING AS A DESATURATION POLICY

Under the Licensing Act 2003 a Council has the power to designate an area within the Borough a “Cumulative Impact Zone” if it feels that the number of licensed premises is having an adverse impact on any of the Licensing Objectives (crime and disorder, noise / nuisance, public safety and harm to children). Given the high number of premises licenses already issued by LBTH, the Council will now adopt a saturation policy for Brick Lane and environs on the basis of the high levels of crime, anti social behaviour and alcohol related harm. Furthermore by increasing the housing provision in Brick Lane, this would ‘dilute’ the relative number of premises licences.

Over the past weekend, a major capital-wide crackdown by the Metropolitan Police on crimes relating to licensing issues resulted in 173 arrests and 44 warrants. Operation Condor, or ‘saturation policing’, was a co-ordinated operation across London from 8am Friday 7 December through to 8am Sunday 9 December, and was run to combat those who flout licensing rules and involved nearly 3,000 officers carrying out 800 activities. One of largest individual operations involved 175 officers, including TSG, the Met helicopter and dog units, carrying out a raid on one of east London’s most popular clubs, 93 Feet East, in Brick Lane… Given the chronic housing shortage that the LBTH Strategic Development Framework has identified, would it not make sense to dilute the saturation of licensed premises by providing more housing stock?

127sho_DESIGN GUIDANCE

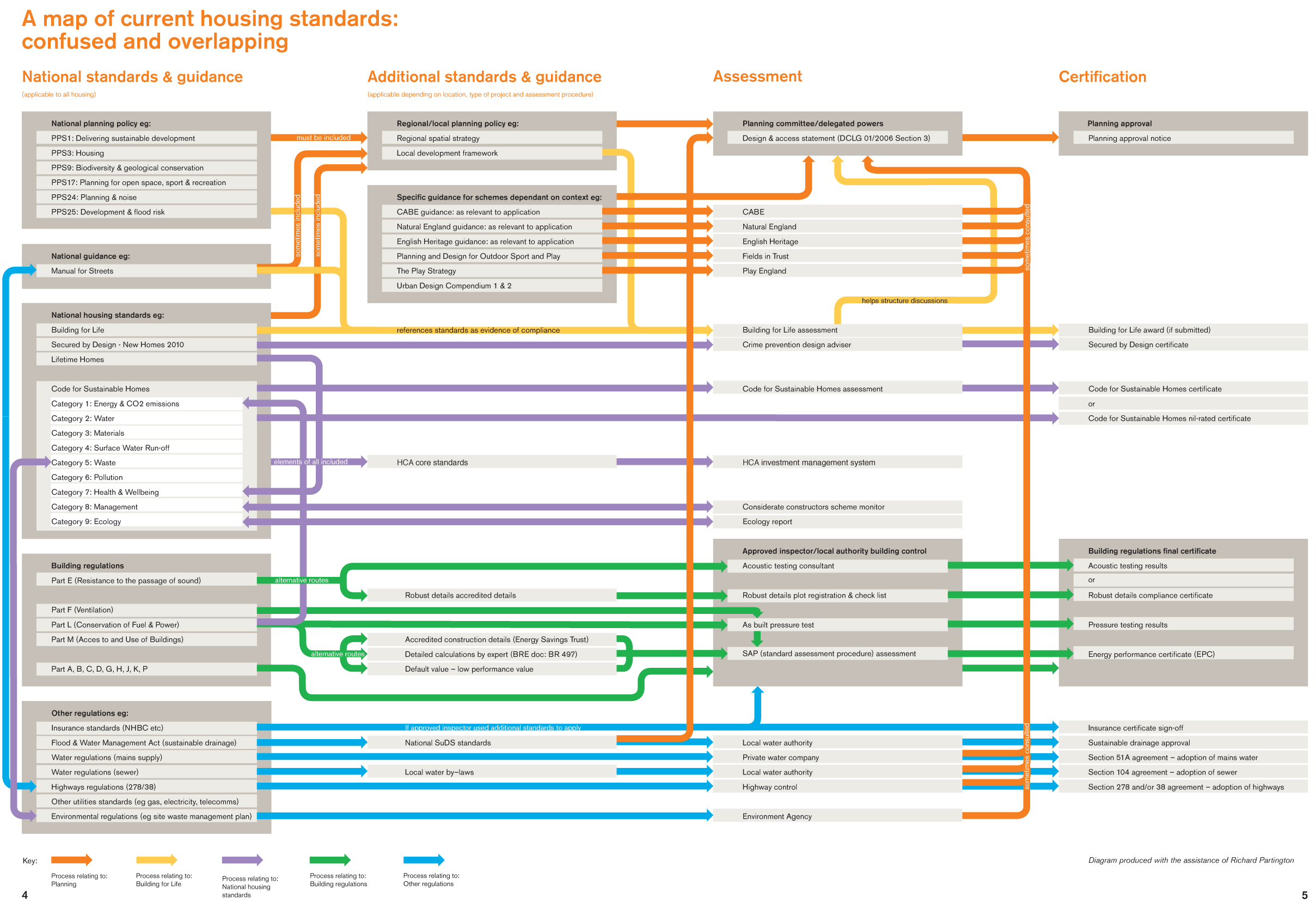

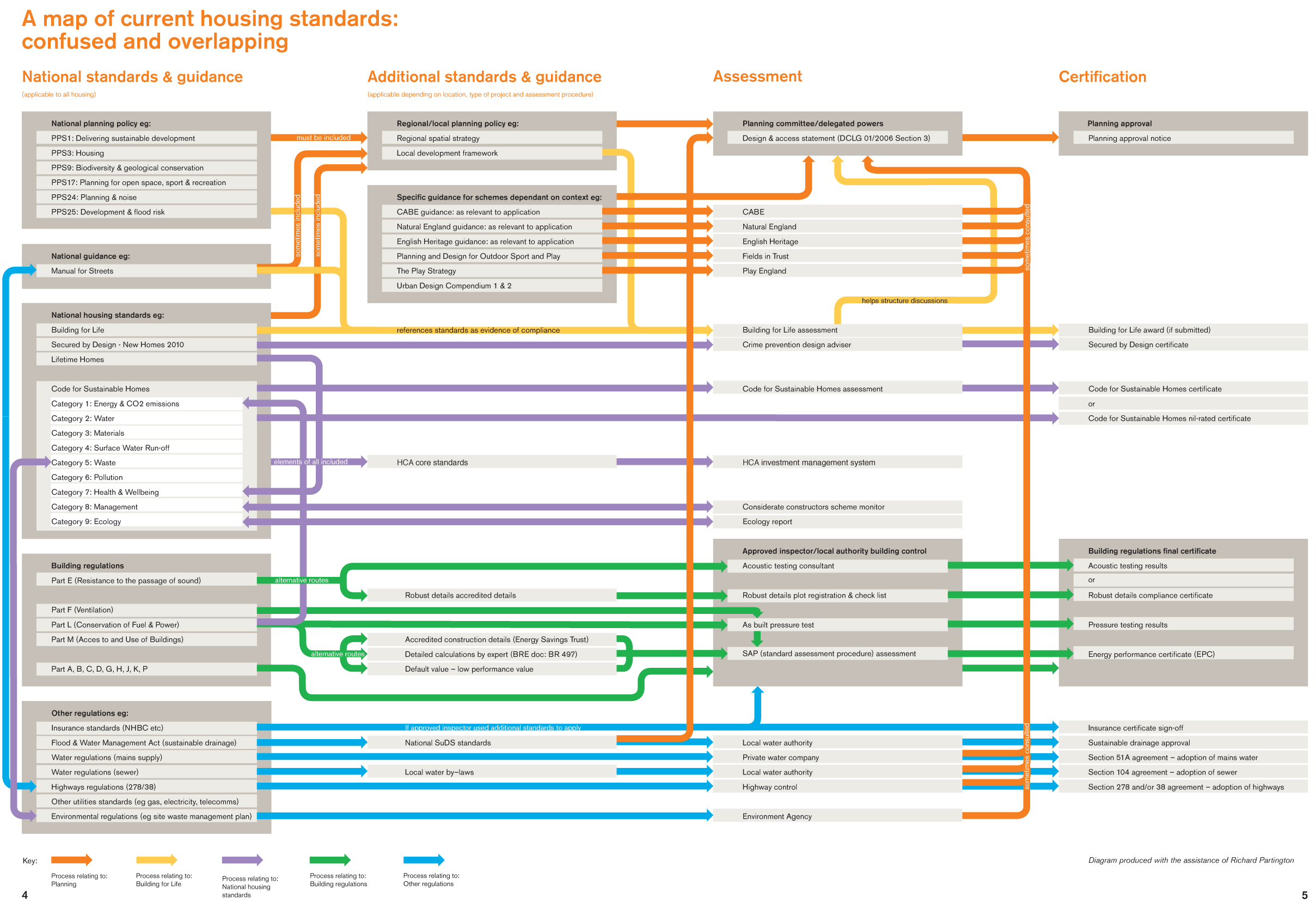

A map of current housing standards shows current guidance to be a confused and overlapping labyrinth…

127sho_Too quiet on the home front

Despite an unprecedented flurry of government initiatives the housing crisis remains grim, with the gap between supply and demand slowly widening. Christine Whitehead (professor of housing economics at the LSE) explains in the RIBA Journal.

The housing situation is pretty depressing – prices are down by perhaps 30% in real terms; additions to the existing stock are running at perhaps half the level required if projected household growth is to be accommodated; and most commentators feel that little of what is being built meets the standards necessary for the next generation. Just as concerning are the likely scenarios were the economy to show signs of significant improvement. If incomes rise then demand for housing will increase against a very limited supply, pushing up prices long before supply can respond; if however credit remains tight, as it has since 2008, then those that can borrow will still put pressure on house prices but first time buyers in particular will find it extremely difficult to enter the market and will be forced to remain in private renting – and pay higher rates.

Current difficulties

The fundamentals behind this inbuilt volatility are relatively straightforward. Unlike some other European countries often held up as exemplars, we have an expanding population with both healthy indigenous growth and continuing net immigration. As a result we need perhaps 230,000 additional dwellings per annum just to accommodate that increase. If fewer units are available young people will have to spend longer at home; more households will have to share or live in overcrowded conditions, especially in London and other areas of economic growth; and both international competitiveness and the quality of life will be undermined. On the other hand, net additions were above 200,000 only at the height of the investment boom in 2007/ 8, and even then new housebuilding output was running at below 170,000. So there has been a continuing shortfall over the economic cycle.

Moreover, what is being produced tends to be smaller than in the past. In 2009, 60% of completions were of one or two bed units, while 50% were flats – most in the market sector. And we do not keep detailed records of the size of units – everything is thought about in terms of the number of rooms, forgetting that the square metres per dwelling have been falling for decades. As households and their needs change, perhaps the innovation which would most influence behaviour might be to ensure that information on square meterage – and cost per metre – was available as a matter of course to all potential purchasers, as it is in every other country in Europe.

Looking ahead

Looking to the future, the biggest problems in the short term are the lack of funds for developers and purchasers both for owner-occupation and private renting; and continued uncertainty about the future economy and housing market, which is reducing demand and supply while leaving the fundamental tensions unaffected. In the longer term there are concerns about loss of capacity in the development industry; the extent to which land prices and expectations are still out of line with underlying equilibrium; and particularly about the extent to which the planning system can ensure adequate land availability.

The government has put forward over 100 initiatives, including: contracts with housing associations and other providers for 170,000 new affordable homes by 2015; public land to be made available for 100,000 homes to be provided on a build now pay later principle; a back stop guarantee system by which 100,000 95% mortgages can be supported; and a further 100,000 additional homes funded from right to buy sales on a one for one basis. Most of these initiatives are relatively short term. The most important longer term initiative is the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) published at the end of March and implemented on the same day.

Future changes

The principles behind the NPPF are clear and potentially game changing. Local authorities with an up to date plan must agree to all proposals that accord with it. Those without a plan must make decisions in line with the framework which gives a presumption in favour of development.

However, one reason for the generally positive response to the NPPF is that the new framework maintains many of the strongest constraints on development, including brownfield first, the emphasis on town centres, constraints on the use of urban public space, the greenbelt and an even greater emphasis on good design. No planning department will have difficulty turning down a development it does not like. It may go through on appeal, but the delays and costs will be high.

The problem is not so much the framework but the fact that 44 documents that supported the existing planning system have been replaced or revoked. Doing away with a thousand pages of detailed guidance leaves stakeholders to work everything out for themselves, and core concepts are generally not defined clearly enough to stop those who dislike the outcomes appealing against planning decisions.

Any large changes in the planning system take a long while to work through – for instance Section 106 was not really fully operational for at least a decade. Even if the pro development agenda does eventually become embedded in the planning system, resulting in higher output, there are sure to be long delays and high costs associated with the new regime.

The housing situation is pretty depressing – prices are down by perhaps 30% in real terms; additions to the existing stock are running at perhaps half the level required if projected household growth is to be accommodated; and most commentators feel that little of what is being built meets the standards necessary for the next generation. Just as concerning are the likely scenarios were the economy to show signs of significant improvement. If incomes rise then demand for housing will increase against a very limited supply, pushing up prices long before supply can respond; if however credit remains tight, as it has since 2008, then those that can borrow will still put pressure on house prices but first time buyers in particular will find it extremely difficult to enter the market and will be forced to remain in private renting – and pay higher rates.

Current difficulties

The fundamentals behind this inbuilt volatility are relatively straightforward. Unlike some other European countries often held up as exemplars, we have an expanding population with both healthy indigenous growth and continuing net immigration. As a result we need perhaps 230,000 additional dwellings per annum just to accommodate that increase. If fewer units are available young people will have to spend longer at home; more households will have to share or live in overcrowded conditions, especially in London and other areas of economic growth; and both international competitiveness and the quality of life will be undermined. On the other hand, net additions were above 200,000 only at the height of the investment boom in 2007/ 8, and even then new housebuilding output was running at below 170,000. So there has been a continuing shortfall over the economic cycle.

Moreover, what is being produced tends to be smaller than in the past. In 2009, 60% of completions were of one or two bed units, while 50% were flats – most in the market sector. And we do not keep detailed records of the size of units – everything is thought about in terms of the number of rooms, forgetting that the square metres per dwelling have been falling for decades. As households and their needs change, perhaps the innovation which would most influence behaviour might be to ensure that information on square meterage – and cost per metre – was available as a matter of course to all potential purchasers, as it is in every other country in Europe.

Looking ahead

Looking to the future, the biggest problems in the short term are the lack of funds for developers and purchasers both for owner-occupation and private renting; and continued uncertainty about the future economy and housing market, which is reducing demand and supply while leaving the fundamental tensions unaffected. In the longer term there are concerns about loss of capacity in the development industry; the extent to which land prices and expectations are still out of line with underlying equilibrium; and particularly about the extent to which the planning system can ensure adequate land availability.

The government has put forward over 100 initiatives, including: contracts with housing associations and other providers for 170,000 new affordable homes by 2015; public land to be made available for 100,000 homes to be provided on a build now pay later principle; a back stop guarantee system by which 100,000 95% mortgages can be supported; and a further 100,000 additional homes funded from right to buy sales on a one for one basis. Most of these initiatives are relatively short term. The most important longer term initiative is the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) published at the end of March and implemented on the same day.

Future changes

The principles behind the NPPF are clear and potentially game changing. Local authorities with an up to date plan must agree to all proposals that accord with it. Those without a plan must make decisions in line with the framework which gives a presumption in favour of development.

However, one reason for the generally positive response to the NPPF is that the new framework maintains many of the strongest constraints on development, including brownfield first, the emphasis on town centres, constraints on the use of urban public space, the greenbelt and an even greater emphasis on good design. No planning department will have difficulty turning down a development it does not like. It may go through on appeal, but the delays and costs will be high.

The problem is not so much the framework but the fact that 44 documents that supported the existing planning system have been replaced or revoked. Doing away with a thousand pages of detailed guidance leaves stakeholders to work everything out for themselves, and core concepts are generally not defined clearly enough to stop those who dislike the outcomes appealing against planning decisions.

Any large changes in the planning system take a long while to work through – for instance Section 106 was not really fully operational for at least a decade. Even if the pro development agenda does eventually become embedded in the planning system, resulting in higher output, there are sure to be long delays and high costs associated with the new regime.

The housing situation is pretty depressing – prices are down by perhaps 30% in real terms; additions to the existing stock are running at perhaps half the level required if projected household growth is to be accommodated; and most commentators feel that little of what is being built meets the standards necessary for the next generation. Just as concerning are the likely scenarios were the economy to show signs of significant improvement. If incomes rise then demand for housing will increase against a very limited supply, pushing up prices long before supply can respond; if however credit remains tight, as it has since 2008, then those that can borrow will still put pressure on house prices but first time buyers in particular will find it extremely difficult to enter the market and will be forced to remain in private renting – and pay higher rates.

Current difficulties

The fundamentals behind this inbuilt volatility are relatively straightforward. Unlike some other European countries often held up as exemplars, we have an expanding population with both healthy indigenous growth and continuing net immigration. As a result we need perhaps 230,000 additional dwellings per annum just to accommodate that increase. If fewer units are available young people will have to spend longer at home; more households will have to share or live in overcrowded conditions, especially in London and other areas of economic growth; and both international competitiveness and the quality of life will be undermined. On the other hand, net additions were above 200,000 only at the height of the investment boom in 2007/ 8, and even then new housebuilding output was running at below 170,000. So there has been a continuing shortfall over the economic cycle.

Moreover, what is being produced tends to be smaller than in the past. In 2009, 60% of completions were of one or two bed units, while 50% were flats – most in the market sector. And we do not keep detailed records of the size of units – everything is thought about in terms of the number of rooms, forgetting that the square metres per dwelling have been falling for decades. As households and their needs change, perhaps the innovation which would most influence behaviour might be to ensure that information on square meterage – and cost per metre – was available as a matter of course to all potential purchasers, as it is in every other country in Europe.

Looking ahead

Looking to the future, the biggest problems in the short term are the lack of funds for developers and purchasers both for owner-occupation and private renting; and continued uncertainty about the future economy and housing market, which is reducing demand and supply while leaving the fundamental tensions unaffected. In the longer term there are concerns about loss of capacity in the development industry; the extent to which land prices and expectations are still out of line with underlying equilibrium; and particularly about the extent to which the planning system can ensure adequate land availability.

The government has put forward over 100 initiatives, including: contracts with housing associations and other providers for 170,000 new affordable homes by 2015; public land to be made available for 100,000 homes to be provided on a build now pay later principle; a back stop guarantee system by which 100,000 95% mortgages can be supported; and a further 100,000 additional homes funded from right to buy sales on a one for one basis. Most of these initiatives are relatively short term. The most important longer term initiative is the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) published at the end of March and implemented on the same day.

Future changes

The principles behind the NPPF are clear and potentially game changing. Local authorities with an up to date plan must agree to all proposals that accord with it. Those without a plan must make decisions in line with the framework which gives a presumption in favour of development.

However, one reason for the generally positive response to the NPPF is that the new framework maintains many of the strongest constraints on development, including brownfield first, the emphasis on town centres, constraints on the use of urban public space, the greenbelt and an even greater emphasis on good design. No planning department will have difficulty turning down a development it does not like. It may go through on appeal, but the delays and costs will be high.

The problem is not so much the framework but the fact that 44 documents that supported the existing planning system have been replaced or revoked. Doing away with a thousand pages of detailed guidance leaves stakeholders to work everything out for themselves, and core concepts are generally not defined clearly enough to stop those who dislike the outcomes appealing against planning decisions.

Any large changes in the planning system take a long while to work through – for instance Section 106 was not really fully operational for at least a decade. Even if the pro development agenda does eventually become embedded in the planning system, resulting in higher output, there are sure to be long delays and high costs associated with the new regime.

The housing situation is pretty depressing – prices are down by perhaps 30% in real terms; additions to the existing stock are running at perhaps half the level required if projected household growth is to be accommodated; and most commentators feel that little of what is being built meets the standards necessary for the next generation. Just as concerning are the likely scenarios were the economy to show signs of significant improvement. If incomes rise then demand for housing will increase against a very limited supply, pushing up prices long before supply can respond; if however credit remains tight, as it has since 2008, then those that can borrow will still put pressure on house prices but first time buyers in particular will find it extremely difficult to enter the market and will be forced to remain in private renting – and pay higher rates.

Current difficulties

The fundamentals behind this inbuilt volatility are relatively straightforward. Unlike some other European countries often held up as exemplars, we have an expanding population with both healthy indigenous growth and continuing net immigration. As a result we need perhaps 230,000 additional dwellings per annum just to accommodate that increase. If fewer units are available young people will have to spend longer at home; more households will have to share or live in overcrowded conditions, especially in London and other areas of economic growth; and both international competitiveness and the quality of life will be undermined. On the other hand, net additions were above 200,000 only at the height of the investment boom in 2007/ 8, and even then new housebuilding output was running at below 170,000. So there has been a continuing shortfall over the economic cycle.

Moreover, what is being produced tends to be smaller than in the past. In 2009, 60% of completions were of one or two bed units, while 50% were flats – most in the market sector. And we do not keep detailed records of the size of units – everything is thought about in terms of the number of rooms, forgetting that the square metres per dwelling have been falling for decades. As households and their needs change, perhaps the innovation which would most influence behaviour might be to ensure that information on square meterage – and cost per metre – was available as a matter of course to all potential purchasers, as it is in every other country in Europe.

Looking ahead

Looking to the future, the biggest problems in the short term are the lack of funds for developers and purchasers both for owner-occupation and private renting; and continued uncertainty about the future economy and housing market, which is reducing demand and supply while leaving the fundamental tensions unaffected. In the longer term there are concerns about loss of capacity in the development industry; the extent to which land prices and expectations are still out of line with underlying equilibrium; and particularly about the extent to which the planning system can ensure adequate land availability.

The government has put forward over 100 initiatives, including: contracts with housing associations and other providers for 170,000 new affordable homes by 2015; public land to be made available for 100,000 homes to be provided on a build now pay later principle; a back stop guarantee system by which 100,000 95% mortgages can be supported; and a further 100,000 additional homes funded from right to buy sales on a one for one basis. Most of these initiatives are relatively short term. The most important longer term initiative is the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) published at the end of March and implemented on the same day.

Future changes

The principles behind the NPPF are clear and potentially game changing. Local authorities with an up to date plan must agree to all proposals that accord with it. Those without a plan must make decisions in line with the framework which gives a presumption in favour of development.

However, one reason for the generally positive response to the NPPF is that the new framework maintains many of the strongest constraints on development, including brownfield first, the emphasis on town centres, constraints on the use of urban public space, the greenbelt and an even greater emphasis on good design. No planning department will have difficulty turning down a development it does not like. It may go through on appeal, but the delays and costs will be high.

The problem is not so much the framework but the fact that 44 documents that supported the existing planning system have been replaced or revoked. Doing away with a thousand pages of detailed guidance leaves stakeholders to work everything out for themselves, and core concepts are generally not defined clearly enough to stop those who dislike the outcomes appealing against planning decisions.

Any large changes in the planning system take a long while to work through – for instance Section 106 was not really fully operational for at least a decade. Even if the pro development agenda does eventually become embedded in the planning system, resulting in higher output, there are sure to be long delays and high costs associated with the new regime.

127sho_EXPANDING FOOTPRINTS

The Torre Valesca by BBPR is part of the first generation of Italian modern architecture, while still being part of the Milanese context in which it was born, to which also belongs the Milan cathedral and the Sforzesco Castle. The tower, approximately 100 metres tall, has a peculiar and characteristic mushroom-like shape. The tower recalls the Lombard tradition of medieval fortresses and towers. In such fortresses, the lower parts were always narrower, while the higher parts propped up by wooden boards or stone beams. Planning laws required that the various programmes within the tower – mixed functions of residential and commercial use – be expressed volumetrically.

A by-product of the mushroom morphology is the urban panorama which an enlarged top floor plate allows. The tower / signal box as an urban periscope? What expanded views might be afforded over Shoreditch? The overlooking of the adjacent park (Allen Gardens) could be enhanced as unnatural surveillance. Or a view to Christ Church framed by a window of steepled proportions?

A by-product of the mushroom morphology is the urban panorama which an enlarged top floor plate allows. The tower / signal box as an urban periscope? What expanded views might be afforded over Shoreditch? The overlooking of the adjacent park (Allen Gardens) could be enhanced as unnatural surveillance. Or a view to Christ Church framed by a window of steepled proportions?

A by-product of the mushroom morphology is the urban panorama which an enlarged top floor plate allows. The tower / signal box as an urban periscope? What expanded views might be afforded over Shoreditch? The overlooking of the adjacent park (Allen Gardens) could be enhanced as unnatural surveillance. Or a view to Christ Church framed by a window of steepled proportions?

A by-product of the mushroom morphology is the urban panorama which an enlarged top floor plate allows. The tower / signal box as an urban periscope? What expanded views might be afforded over Shoreditch? The overlooking of the adjacent park (Allen Gardens) could be enhanced as unnatural surveillance. Or a view to Christ Church framed by a window of steepled proportions?

127sho_SIGNAL BOX?

127sho_Shoreditch Overground.

If form follows function, what happens when the intended purpose of a space becomes obsolete? When a building’s use is no longer required? Does form follow function out the door? Let’s look at another brick station for answers. Bankside Power Station closed in 1981 due to rising oil prices and after 29 years of providing power. Then after 19 years of inactivity the building reopened as the Tate Modern in 2000 and 13 years later, it is fair to say, the buildings ‘second life’ as an artspace has triumphed its original purpose.

The social theorist Baudrillard would describe a building that loses its use as a signifier. A hollow space containing only symbols of a former existence. Shoreditch Station without the railways is ironically just ‘a signal box’. A loss of original use does not however have to signal a loss of value so, with a headnod to English Heritage’s ‘logical approach to the historic environment’ our SoS identifies that whilst the station has no historic, evidential or architectural value, it does retain a communal value. And it was for this reason we argued that the former station, less a building than a chattel, should be elevated on top of the new development.

For Shoreditch Station, the proposal to elevate the station to a higher ground is made meaningful when we realise that the ground beneath the station’s feet has already been swept away. The railway tracks and double-height vaulted walls were demolished to make way for the East London extension. The UCL Institute of Archeology has suggested that the station was never a building after all, as it is without foundations (the station structure sits on 6 steel beams spanning over non-existent platforms and tracks: the station’s purpose was derailed some time ago by TfL. So today the station sits above hollow ground, as a signifier of a time when it was once a station. A ghost building for ghost trains.

The story of Shoreditch Station is not only one of recession but also optimism. It needs to have a use that, like the neighbourhood it is situated in, is diurnal. Yet unlike the current scenario in Brick Lane, the station’s future use requires a diurnality that is not a fast-speed schizophrenia between daytime-shopping and nighttime-drinking, a slower space that embraces art and housing. Housing normalises a neighbourhood saturated with entertainment licences. And art , as evident in the streets and on the station, can provide new signs of tomorrow. Shoreditch Station already has an accidental new use as a focal point along street art tours. Whether the heritage vs art house strategy is manifest as old crowning the new, or it’s polar opposite, new bearing down on the old, it doesn’t really matter as long as there are both signs of the past and future omnipresent.

For Shoreditch Station, the proposal to elevate the station to a higher ground is made meaningful when we realise that the ground beneath the station’s feet has already been swept away. The railway tracks and double-height vaulted walls were demolished to make way for the East London extension. The UCL Institute of Archeology has suggested that the station was never a building after all, as it is without foundations (the station structure sits on 6 steel beams spanning over non-existent platforms and tracks: the station’s purpose was derailed some time ago by TfL. So today the station sits above hollow ground, as a signifier of a time when it was once a station. A ghost building for ghost trains.

The story of Shoreditch Station is not only one of recession but also optimism. It needs to have a use that, like the neighbourhood it is situated in, is diurnal. Yet unlike the current scenario in Brick Lane, the station’s future use requires a diurnality that is not a fast-speed schizophrenia between daytime-shopping and nighttime-drinking, a slower space that embraces art and housing. Housing normalises a neighbourhood saturated with entertainment licences. And art , as evident in the streets and on the station, can provide new signs of tomorrow. Shoreditch Station already has an accidental new use as a focal point along street art tours. Whether the heritage vs art house strategy is manifest as old crowning the new, or it’s polar opposite, new bearing down on the old, it doesn’t really matter as long as there are both signs of the past and future omnipresent.

For Shoreditch Station, the proposal to elevate the station to a higher ground is made meaningful when we realise that the ground beneath the station’s feet has already been swept away. The railway tracks and double-height vaulted walls were demolished to make way for the East London extension. The UCL Institute of Archeology has suggested that the station was never a building after all, as it is without foundations (the station structure sits on 6 steel beams spanning over non-existent platforms and tracks: the station’s purpose was derailed some time ago by TfL. So today the station sits above hollow ground, as a signifier of a time when it was once a station. A ghost building for ghost trains.

The story of Shoreditch Station is not only one of recession but also optimism. It needs to have a use that, like the neighbourhood it is situated in, is diurnal. Yet unlike the current scenario in Brick Lane, the station’s future use requires a diurnality that is not a fast-speed schizophrenia between daytime-shopping and nighttime-drinking, a slower space that embraces art and housing. Housing normalises a neighbourhood saturated with entertainment licences. And art , as evident in the streets and on the station, can provide new signs of tomorrow. Shoreditch Station already has an accidental new use as a focal point along street art tours. Whether the heritage vs art house strategy is manifest as old crowning the new, or it’s polar opposite, new bearing down on the old, it doesn’t really matter as long as there are both signs of the past and future omnipresent.

For Shoreditch Station, the proposal to elevate the station to a higher ground is made meaningful when we realise that the ground beneath the station’s feet has already been swept away. The railway tracks and double-height vaulted walls were demolished to make way for the East London extension. The UCL Institute of Archeology has suggested that the station was never a building after all, as it is without foundations (the station structure sits on 6 steel beams spanning over non-existent platforms and tracks: the station’s purpose was derailed some time ago by TfL. So today the station sits above hollow ground, as a signifier of a time when it was once a station. A ghost building for ghost trains.

The story of Shoreditch Station is not only one of recession but also optimism. It needs to have a use that, like the neighbourhood it is situated in, is diurnal. Yet unlike the current scenario in Brick Lane, the station’s future use requires a diurnality that is not a fast-speed schizophrenia between daytime-shopping and nighttime-drinking, a slower space that embraces art and housing. Housing normalises a neighbourhood saturated with entertainment licences. And art , as evident in the streets and on the station, can provide new signs of tomorrow. Shoreditch Station already has an accidental new use as a focal point along street art tours. Whether the heritage vs art house strategy is manifest as old crowning the new, or it’s polar opposite, new bearing down on the old, it doesn’t really matter as long as there are both signs of the past and future omnipresent.