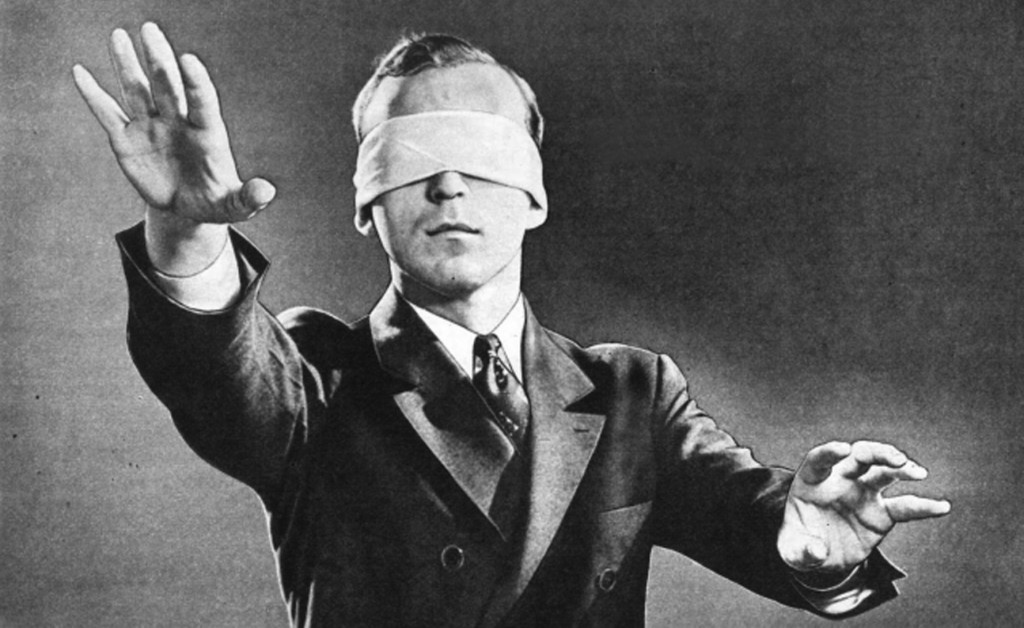

000off_BLIND-FOLDED CRITIQUE / DARK-ITECTURE

blablablarchitecture is talking buildings. This posits listening to architecture over looking at architecture.

‘Blindfold Critique’ is a new way of looking at architecture. Or rather not looking at architecture in that it goes beyond the visual and into the aural. An architect or critic is blindfolded, and taken to an architectural site, where they are asked to give their critique as they are led through the architecture. These critiques have been recorded and edited by Joshua David Lynch and are presented here as audio files (and best listened to through headphones).

Blindfold Critiques where done as part of the 2013 Sydney Architecture Festival and were presented as part of the Expanded Architecture at The Rocks Exhibition.  Following on from BlindFold Critiques is this essay Dark-itecture by SOPHIA BANNERT which won the AJ Writing Prize 2014. Architecture doesn’t always engage all of our senses, and tends to rely heavily on sight; appearance rules over experience. Architecture continues to be theorised and practised as an art form of the eye. As a result, it is dominated by considerations such as visual harmony, the divine proportion and the golden ratio. Throughout history, buildings have mostly been about visual seduction to be marvelled at, rather than skilful arrangements of materials and sensations, to create comfortable and inspiring places for everyday use. It’s right that they should be visually stimulating, but let’s not forget our other senses. With the right formula appealing to all of our senses, architecture holds the power to influence your feelings towards a space, your mood, and how you feel about yourself, on a subconscious level. A good architect should be aware of this. Danish architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen said the job of the architect is to ‘remain anonymously in the background, resembling the theatrical producer. He composes the music others will play.’ Composing inspirational and stimulating atmospheres is more effective when an orchestra of senses is involved. This led me to question how rich spaces can be when we take something as predominant as vision out of the equation. A visit to the French restaurant Dans le Noir? provided me with an ensemble of sensory experiences by removing my sense of sight, thus heightening my other senses. The restaurant is unique in the fact that the waiters are visually impaired. The guest is served in complete darkness which reignites one’s sensory and spatial awareness. For once, the blind can act as your eyes, guiding you through the (step-free) experience. The digital revolution makes it difficult to pay attention to the present moment. Therefore, no electronic devices are allowed in, which could serve as distractions. My initial reaction was one of disorientation and unease; deprivation of sight can be frightening. Our eyes are responsible for 80 per cent of the information our brain receives. This makes it the most vital sensory input of the human body. Take that away and the brain is forced to rely on its other senses. Sound is the second most important sense and without sight I was profoundly aware of the acoustics: melodic jazz in the background, mixed with conversational murmurings. Carpet beneath my feet, I reached my hand out and touched a wall which was divided, the top half seemed to have a material covering, and halfway down I felt what I thought must have been heavy wallpaper. The table cloth felt like linen, and I sat in a leathery chair. The room seemed intimate and private, with few other people. Surprisingly the room actually served 60 people. How interesting that when sound is muted and sight removed, one’s spatial awareness can be so wrong. During the meal, I become acutely more aware of the way I was using my voice in conversation. (How do you convey a smile in the dark?) Pitch, speed, volume and tone of voice were suddenly crucial for communication. (Nodding my head in agreement was a wasted gesture – yet I still found myself doing it.) Conversation became an art once more and I felt it was more meaningful. I felt at ease and confident. Visual limitations became liberating. Being became much simpler. I entered a space devoid of vanity; shyness conquered. In this room sensory perception was magnified and, with the removal of sight, style became meaningless. Juhani Pallasmaa once said: ‘Architecture is a slow and silent background phenomenon that frames human experience and gives it specific horizons of meaning. This silent but perpetual presence is the special monumental power of the art of architecture.’ If architects were blind, spaces would be more ergonomic and logical; design of the human experience would be crucial. The architecture here is the feeling created. The light scent of food increased my appetite and anticipation of what I was about to eat. Odours are chemicals which powerfully affect our brain function; influencing mood shifts and triggering involuntary memories and feelings. The smell of good food triggered, for me, associations with homely comfortable memories, which furthered the relaxed ambience. My entire perception of time disappeared whilst I was in the room. Can a space alter the way time is perceived? Neuroscientist David Eagleman states that when we hear enjoyable sounds and experience new sensations, the greater attention we pay leads to perception of a longer period of time. ‘When familiar information is processed, this doesn’t take much time at all. New information however, is a bit slower to process and makes time feel elongated.’ The concept of a space altering our perception of time is thought provoking. We live such busy lives; it would be wonderful to be able to create the illusion of slowing time down to enjoy the present. Without romanticising being blind, my visit to Dans le Noir? raised my awareness of the importance of our environments, and the way in which we perceive them, in a way no other place could, by allowing one’s other senses to fully engage in the environment – without the overriding reliability on sight. The genius-loci or spirit of place is easier to feel than see. Our over-connected environments are becoming sensory impoverished and lack inspirational non-visual stimuli. Modern digital culture can conflict with meaningful human communication. Can we, as architects, address this isolation by creating spaces in which people can reconnect on a more intimate level? To open a restaurant in which one dines in complete darkness was a courageous act, but in doing so they have provided the diner with a banquet of sensory stimuli. It’s an irony that if a sense is taken away, one can become more sensually aware. To quote Marcel Proust: ‘The real act of discovery consists not in finding new lands, but in seeing with new eyes.’ Guests leave with a new found multisensory awareness, to perhaps rediscover something lost.’

Following on from BlindFold Critiques is this essay Dark-itecture by SOPHIA BANNERT which won the AJ Writing Prize 2014. Architecture doesn’t always engage all of our senses, and tends to rely heavily on sight; appearance rules over experience. Architecture continues to be theorised and practised as an art form of the eye. As a result, it is dominated by considerations such as visual harmony, the divine proportion and the golden ratio. Throughout history, buildings have mostly been about visual seduction to be marvelled at, rather than skilful arrangements of materials and sensations, to create comfortable and inspiring places for everyday use. It’s right that they should be visually stimulating, but let’s not forget our other senses. With the right formula appealing to all of our senses, architecture holds the power to influence your feelings towards a space, your mood, and how you feel about yourself, on a subconscious level. A good architect should be aware of this. Danish architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen said the job of the architect is to ‘remain anonymously in the background, resembling the theatrical producer. He composes the music others will play.’ Composing inspirational and stimulating atmospheres is more effective when an orchestra of senses is involved. This led me to question how rich spaces can be when we take something as predominant as vision out of the equation. A visit to the French restaurant Dans le Noir? provided me with an ensemble of sensory experiences by removing my sense of sight, thus heightening my other senses. The restaurant is unique in the fact that the waiters are visually impaired. The guest is served in complete darkness which reignites one’s sensory and spatial awareness. For once, the blind can act as your eyes, guiding you through the (step-free) experience. The digital revolution makes it difficult to pay attention to the present moment. Therefore, no electronic devices are allowed in, which could serve as distractions. My initial reaction was one of disorientation and unease; deprivation of sight can be frightening. Our eyes are responsible for 80 per cent of the information our brain receives. This makes it the most vital sensory input of the human body. Take that away and the brain is forced to rely on its other senses. Sound is the second most important sense and without sight I was profoundly aware of the acoustics: melodic jazz in the background, mixed with conversational murmurings. Carpet beneath my feet, I reached my hand out and touched a wall which was divided, the top half seemed to have a material covering, and halfway down I felt what I thought must have been heavy wallpaper. The table cloth felt like linen, and I sat in a leathery chair. The room seemed intimate and private, with few other people. Surprisingly the room actually served 60 people. How interesting that when sound is muted and sight removed, one’s spatial awareness can be so wrong. During the meal, I become acutely more aware of the way I was using my voice in conversation. (How do you convey a smile in the dark?) Pitch, speed, volume and tone of voice were suddenly crucial for communication. (Nodding my head in agreement was a wasted gesture – yet I still found myself doing it.) Conversation became an art once more and I felt it was more meaningful. I felt at ease and confident. Visual limitations became liberating. Being became much simpler. I entered a space devoid of vanity; shyness conquered. In this room sensory perception was magnified and, with the removal of sight, style became meaningless. Juhani Pallasmaa once said: ‘Architecture is a slow and silent background phenomenon that frames human experience and gives it specific horizons of meaning. This silent but perpetual presence is the special monumental power of the art of architecture.’ If architects were blind, spaces would be more ergonomic and logical; design of the human experience would be crucial. The architecture here is the feeling created. The light scent of food increased my appetite and anticipation of what I was about to eat. Odours are chemicals which powerfully affect our brain function; influencing mood shifts and triggering involuntary memories and feelings. The smell of good food triggered, for me, associations with homely comfortable memories, which furthered the relaxed ambience. My entire perception of time disappeared whilst I was in the room. Can a space alter the way time is perceived? Neuroscientist David Eagleman states that when we hear enjoyable sounds and experience new sensations, the greater attention we pay leads to perception of a longer period of time. ‘When familiar information is processed, this doesn’t take much time at all. New information however, is a bit slower to process and makes time feel elongated.’ The concept of a space altering our perception of time is thought provoking. We live such busy lives; it would be wonderful to be able to create the illusion of slowing time down to enjoy the present. Without romanticising being blind, my visit to Dans le Noir? raised my awareness of the importance of our environments, and the way in which we perceive them, in a way no other place could, by allowing one’s other senses to fully engage in the environment – without the overriding reliability on sight. The genius-loci or spirit of place is easier to feel than see. Our over-connected environments are becoming sensory impoverished and lack inspirational non-visual stimuli. Modern digital culture can conflict with meaningful human communication. Can we, as architects, address this isolation by creating spaces in which people can reconnect on a more intimate level? To open a restaurant in which one dines in complete darkness was a courageous act, but in doing so they have provided the diner with a banquet of sensory stimuli. It’s an irony that if a sense is taken away, one can become more sensually aware. To quote Marcel Proust: ‘The real act of discovery consists not in finding new lands, but in seeing with new eyes.’ Guests leave with a new found multisensory awareness, to perhaps rediscover something lost.’

SAY WHAT_!?